India’s urban population, projected to be ~950 million by 2050 from ~480 million in 2020, indicates (even by conservative estimates) that it will have nearly doubled by 2050.

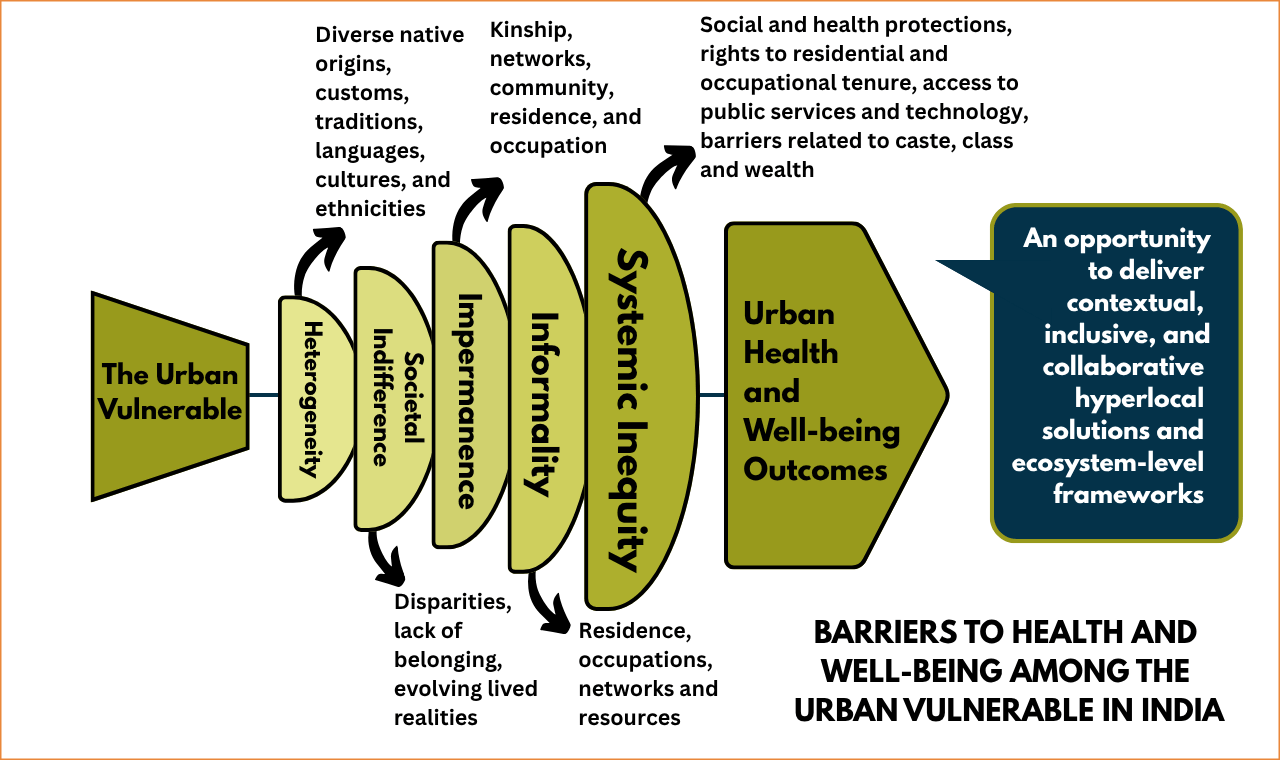

Experiences from the COVID-19 pandemic fore fronted stark realities and vulnerabilities of the urban landscape – heterogeneity, societal indifference, impermanence, informality, and systemic inequities. These factors (continue to) determine consequences for low-income populations in urban settings that include poor living and sanitation conditions, food and transportation insecurity, limited availability of and access to health care services, and an increasing disease burden. [The urban vulnerable face the conflated burden of communicable diseases, non-communicable diseases, and violence and injuries. The National Family Health Survey (NFHS)-5 (2019-21) reveals stark disparities in urban health, with under-five mortality rate among the poorest urban populations at 63 deaths per 1,000 live births, compared to the national average of 32.]

The public health sector’s focus in the urban health space remains fragmented and siloed. Barriers to health care among the urban vulnerable include affordability of, access to, and availability of equitable, quality, and inclusive health care services. Challenges in access are further exacerbated by financial constraints, limited health literacy, deficient public infrastructure, and stigma and discrimination.

This complex, multi-dimensional, and layered picture underscores the need for contextual, comprehensive, inclusive, and collaborative ecosystem-level solutions as India (and the world) moves steadily towards the reality of a highly heterogeneous and overwhelmed urban landscape.